issue 01: school’s out

breakfast 2020

This first issue of Plates: An experimental journal of art and culture presents seven pieces that scrutinise the educational institution. Across a range of forms including poetry, critical essays, and comics, the contributors to Issue 01: School’s Out critically reflect on the institution as we knew it, as we know it, and as we could know it.

Plates Issue 01 is available via our stockists. Though we also offer online editions of each contribution (available below), purchase the print edition for the full Plates experience. All sales go directly towards printing costs and contributor fees.

Contents:

- Letter from the Editor

- Respect for Hands by Ree Sherwood

-

NO MORE MR. NICE GUY by Itzel Basualdo

-

To Each Generation a Campus is Born by Ali Tomek

-

Resisting Education with The Simpsons by Theo MacDonald

-

because if by Johanna Tesfaye

-

An Interview with Compound Yellow by Leah Gallant

-

Towards a Future Practice by Tomorrow-Mañana

Contributors:

Itzel Basualdo is an interdisciplinary artist from Miami, Florida. She hated the place for many years, severely missed it while she was away in graduate school, but has now returned to Miami and her disdain. Her practice often involves photography, video, installation, text, sometimes all at the same time. Her work has appeared in The Acentos Review, The MFA Years, Sinking City Lit Mag, Creative Nonfiction, Saw Palm Magazine, Ginger, and the documents folder on her laptop. She holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is currently the Youth Programs Coordinator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

Leah Gallant is an artist and writer from Cambridge, Massachusetts. She holds degrees from Swarthmore College and Illustrious Kumquat University, and is currently a master’s candidate in Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Theo MacDonald completed a BFA (Hons) at the University of Auckland in 2016, and is now based in Toronto. His research interests include the formal histories of media technology and video collage. He co-hosted the radio program Artbank on 95bFM from 2016 to 2018, and co-founded the noise bands PISS CANNONN, 3 Chocolatiers, and LONDON DRUGS. He has contributed written work to SADO Journal, HAMSTER Magazine, and METRO Magazine. Recent exhibitions include Stop the World From Spinning (KNULP, Sydney), Heart of Glass (Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington), and The Tomorrow People (Adam Art Gallery, Wellington).

Ree Sherwood holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and reads for Carve magazine. Ree comes from Western Pennsylvania and wants to tell you all about it. Find more work in Painted Bride Quarterly, Lavender Review, and Rivet.

Johanna Tesfaye is a Black conceptual artist from Central Illinois. With a background in communication design, her work uses text as a dynamic and performative structure to explore language, space, identity, and collective memory/experience. Patterning elements, such as repetition, play a key role in the forms she creates. The text loop, a recurring theme in her work, is an invitation to challenge the way the viewer enters the piece, considers their positionality, and makes meaning of the content. She is currently based in Chicago, pursuing her Master of Arts in Art Therapy and Counseling at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Ali Tomek is a writer, graphic designer, and educator living in Chicago. She is the author of the science-fiction novel When Something Solid Collapses Under Itself and has written about city anxiety, airplane design, and the Eclipse. She graduated from Northwestern University in 2016 and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019.

Tomorrow-Mañana is a collective exercise in resistance against current dominating ideologies and manifestations of architecture in America and by reflection the world. The project, which results from the conflict between what we desire and deserve as compared to the world we find ourselves inhabiting, is a structured dissemination of discourse challenging our current practices, labour, and identity as both architects and citizens alike. Tomorrow-Mañana exists through interventions in physical space, questions posed to panels, graphic projects, and critical reflections; together we work to build the framework of tomorrow through a critique of today.

letter from the editor

Grass at Columbia University, circa May 2017. Courtesy Unyimeabasi Udoh.

Grass at Columbia University, circa May 2017. Courtesy Unyimeabasi Udoh.

Where Plates co-founder Unyimeabasi Udoh went to college was a very pretty place: Columbia University, the largest landowner in New York City.1 Nestled in all this land is a set of very beautiful lawns. How do they keep their lawns so beautiful? They have a system.

First—as with many systems we would like to criticise—they have a fence. The fences are low; you could maybe jump them, except that around the fences are hedges. Also, you would get yelled at.

Second—and again as with many systems we would like to criticise—there are flags. Red flags and green flags indicate when you do (green) or do not (red) have permission to enter the lawn. But these flags almost always run red: they’re red after it rains, before it might rain, all through the winter, and whenever it strikes groundskeeping’s fancy. Really there are only about two weeks when the lawns are open: one in spring and another in fall, when parents are in town and are wont to do what they are wont to do with the lawns for which they claim to have paid. Perhaps there is greater access over summer, when students are elsewhere, but Udoh cannot attest to that.

In order to preserve the lawns over winter, the school wraps them in what is formally called a “turf blanket” but anyone you might ask calls “lawn condoms”: white custom tarps that have holes cut out for trees. When the snow falls on the lawn condoms you cannot tell from a distance what is condom and what is snow.

When spring comes, the school removes the condoms and— success!—the lawns are beautiful. We gaze on ye mighty and think, maybe all the restrictions are worth it. Young lads ready their croquet mallets, salmon-coloured shorts, and Lacoste polos and all seems right with the world for a moment. But then it comes time for graduation, and the school rolls its fake grass over its real grass, puts the graduation bleachers on top, and leaves it that way for a month.

Of course, suffocated for so long, the real grass dies, so after graduation they pull it all out and replace it with new grass.

Meanwhile, in 2018, 51 of 54 of Columbia University’s Visual Art graduates met with their Provost and Dean, demanding full tuition refunds, citing absentee instructors and studios with flooding issues, temperatures that match a sweltering summer day or else a cold winter morning, and crumbling ceilings. Even though the Provost reportedly agreed with the students that the programme is a “disgrace,” no refund was given.2

The state of the lawns during this meeting could not be confirmed, but according to the schedule it was likely in or approaching the “fake grass” section of the cycle.

Though recent articles on Columbia University’s Facilities and Operations website would have you believe greater access has been granted to these lawns since Udoh’s graduation,3 we’re not really talking about lawns, are we. Well, we are (these lawns are ridiculous), but we’re also talking about the logic of the institution.

Both of us graduated from MFA programmes4 in 2019. While there is a lot we could speak warmly of in regards to our cumulative 37 years in school—especially of having met each other—the system is pretty rotten.

This first issue of Plates: An experimental journal of art and culture presents seven pieces that scrutinise the educational institution. We invited contributors to critically reflect on the institution as we knew it, as we know it, and as we could know it.

Thank you so much for reading Plates Issue 1: School’s Out. In order to remain exactly as we would like, Plates is not held under the wing of any institution. However, this also means we rely on the income generated from our store and donations towards the publication’s continued financial solvency. Please consider making a contribution.

Thank you for choosing us for your most important meal of the day / Bon appétit / Eat that up, it’s good for you,5

Casey Carsel and Unyimeabasi Udoh

1 By number of addresses owned, after the city itself. See Tanay Warerkar, “New York’s 10 biggest property owners,” Curbed NY, 14 September 2018.

2 Benjamin Sutton, “Columbia University MFA Students Demand Tuition Refunds,” Hyperallergic, 30 April 2018.

3 “As Fall Semester Comes to a Close, Presence of Green Flags on Lawns Is the Norm,” Columbia University Facilities and Operations, 11 December 2017.

4 Well, the same one, or two different departmental heads of the same art-school Hydra; we’re not naming names, but we’re sure you can figure it out.

5 Two Door Cinema Club, “Eat That Up, It’s Good For You,” YouTube, 30 January 2010.

respect for hands

ree sherwoodThere were no mirrors in the McDonald’s on Forbes and Atwood in Pittsburgh. I never knew how I looked in my uniform, always getting dressed in the barely-morning. The smallest pants they had still tightened around my ribcage like a draw-string bag. I’d wait for the last possible moment to lower the visor over my French braid and put on the customer service smile I was still learning.

That summer, just after my freshman year at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), I took a poetry workshop and read nothing but sad, cheeky memoirs by gay men (Augusten Burroughs, David Sedaris). I read Running with Scissors for the sixteenth time just to get to the chapter where Augusten’s best friend, Natalie, becomes a McDonald’s counter kid too. Connected by the polyester swaddling, I admired her. She strolled around Cape Cod in that uniform, watching for whales but only finding plastic bags.

︎

I was one of the lucky kids who had the chance to leave our town of working hands for a new-Ivy tech school just seventy miles south of my childhood bedroom.

On move-in day, after I said goodbye to my parents in the parking garage off Forbes and Meyran, I stood to watch the president speak. Look around you, he said. Everyone here was the best in high school. But now you’re all the same.

A level playing field, I’d soon learn, was too kind a sentiment. Not quite the traditionally prestigious institution, the school loved pointing to its own chest and claiming innovation. It was soon clear who, exactly, the school herded through its hallways to show off at the end of a long few years. Under Carnegie Mellon’s watch, the computer science majors were always sleeping on benches near computer clusters; the architecture majors slept only one day each month, and they’d sleep straight through it; the engineers ran the school, boasting guaranteed jobs; the opera singers and actors glided beautifully into their marble-lined College of Fine Arts; and the writing kids, we began to learn the art of self-deprecation.

In the beginning—before Carnegie Tech knew the Mellon Institute—the school was meant to educate for the steel industry. It was intended for what Carnegie’s grandfather, Thomas Morrison, cutely called “Handication.” Rather than filling the young heads with knowledge you can’t touch, students were meant to learn how to use their hands and join the higher-ranking employees of industry. Pittsburgh in the 1900s, so heavy with steel that the entirety of its land was covered in constant soot and smoke. White-collar men had to change their shirts every time they went outside. The city was made for labourers, and Carnegie made the school for them.

“CMU doesn’t imagine the future,” its website boasts, “we create it.”

That summer, I couldn’t stop writing. For no one. For me. I couldn’t understand it: the body-tired; the wasted food; the way no one could look at me; the construction workers from down the street who spent every night sleeping in their trucks; 4:00am, the fact of it, how we would all continue to get out of bed and come in through those doors off Forbes and stand around while someone on the radio kept singing Happy, I’m happy, happy.

My being hired at McDonald’s, I’m pretty sure, was their mistake. Every job post I found asked for experience, but to find experience you need a job. This impossible cycle led me to the McDonald’s ketchup-and-mustard branded online form. I didn’t read the application instructions for their sliding scale questionnaire and there was no way back; I still don’t know if they hired me or my exact opposite.

I have to tell you, I only lasted for two months as a counter kid. I quit quickly, over the phone, in my dorm-room bed at 3:00am. When it was over, I sat in the dark living room, slowly peeling the skin from an orange, letting its light breath hiss onto my thumb.

In eighth grade, we had the terror and joy of being in Mrs. R.’s history class. She was a badass legend in our junior/senior high school. Sitting in the seventh-grade history teacher’s class next door, you could hear her yelling. Egyptians mummies lost their interest, and everyone wanted to know who was the recipient of one of her famous beratings.

I wouldn’t say she ever mocked us. It was always a care-filled jeering that, I’m sure, shielded her own mental well-being as an eighth-grade history teacher in a school with only a dozen outdated textbooks for 150 kids. The cruelest thing she ever did was make all eight of us in her first-period class stay standing after the pledge of allegiance to sing a Groundhog Day song. Twice. Despite the mocking and berating—or maybe because of it—Mrs. R. was largely the favourite.

Towards the beginning of the year, one kid made a joke that someone would end up serving fries at McDonald’s. It was an insult. And Mrs. R., with an urgency I had not heard before, yelled across the room, Don’t say that. Her cheeks blared. Her father, she told us, raised their whole family delivering milk crates. All work is to be respected. There’s no shame in whatever work supports you.

There weren’t many options in my hometown. We were raised by public school teachers, firefighters, house painters, hairdressers, cashiers, caretakers. We are the kind of people who get by with our hands.

I’ve found that institutions don’t have much respect for hands. University is a place where you could forget your body completely, if you wanted to.

︎

That summer I took my first poetry class, with non-slip shoes packed tight in my bag and whipped cream still crusted under my nails. I was not yet used to the slippage between work and school or who I was in either place. Our professor led us upstairs and crammed all seven of our bodies into her windowless office. She turned the lights out. We were whistling lungs and fingertips a touch uncomfortable in their own bones. Darkness and breath and the tricks played by the mind. The lights turned back on, only sixty seconds. Everything I know about poetry will always come back to this—the strange closeness of strangers in the dark, when you can feel the heat from a summerskin shoulder without ever touching.

Each hand has a total of twenty-seven bones: three in each finger, two in each thumb, lined with the five bones in the middle of the hand (metacarpal), down to the eight-bone wrist structure (carpal). Sometimes, now, when passing a beer to a customer, our fingers will meet around the cold glass.

That summer, it wasn’t uncommon for someone to not show up for work. Memorial Day left me alone at the registers with the manager—a kind, soccer-mom sort of woman. She brought in Twizzlers for us. 6:00am and we passed the bag between us and the kitchen crew. They were the kind that twisted every colour of the rainbow. One of the coffee regulars came up to me, waving his Styrofoam cup. You really gonna charge me? he said. I held out my hand for his quarters. He took the cigarette from behind his ear, let it hang between his teeth as he walked out the double doors. He leaned against the front window with his coffee and cigarette. I stayed at the counter with my stolen bites of Twizzlers. We watched Pittsburgh wake up.

︎

I found so little quiet in school. Even the library, all those books and work, it can be so loud. I can’t think unless I’m cleaning the stove or walking up steady hills. I can’t think until I can feel my toes, how firmly I fit inside of them.

That summer, I learned to not fear the dark hours of Pittsburgh. All the monsters show themselves in the daylight. The city between dusk and dawn was always kind. The streetlamps flickered like candles in a cool home. I would wrap my cardigan around my polo until I reached the flickering golden arches.

Upon a cursory Google search of “working through college” I find that I am either ahead of the game or irrevocably fucked.

Please excuse a moment of bitterness: the desire to leave my hometown for good led to fifty-hour work weeks through school led to no time for internships led to this sinking feeling that my degree has qualified me for nothing without those extra hours of free labour. Graduation comes and the question keeps popping up, “What do you want to do with that?” I’ve learned to walk away.

I want resources for full-time students working long hours off-campus: special nap benches; support groups that meet at odd hours, say, 3:00am for the bakers and bartenders; free snack bins; a communal fridge where the restaurant workers bring back leftovers to share with the group. Something to keep us around, to acknowledge how easy it becomes to dream of dropping out.

Every one of my cover letters, now, read like lonely love notes To Whom It May Concern.

An undergrad fiction workshop instructor who was prone to pounding on the table in heated rants told us to never list all the jobs we’ve worked in our bios. We all do whatever we can to get by, she said. I was twenty and saving up to study abroad. By that point I had had gigs as a house cleaner, chapel cleaner, tutor, McDonald’s counter kid, bill collector, restaurant host and (eventually) server, and office assistant/professional cart-pusher. I was proud of this list. All the odd titles I got to carry for a little while.

Please excuse a moment of frankness: if you’ve never had to ask with a straight face, Would you like fries with that, some days I can’t even talk to you.

I’m growing tired of apologising for studying writing. I’m certainly tired of apologising for working service positions. It’s temporary, I’ve learned to say. Here until the next thing. But that thought remains: because I spent money on this education, shouldn’t I be reaching higher? Trying to peek onto the next shelf: university teaching positions, journalism, the vague but well-dressed field of “publishing.”

I am so grateful for the work I’ve done. This work has taught me kindness—something rarely found in universities. The passing faces of tables. We often spend only an hour exchanging pleasantries and practiced jokes, if that. Strangers retaining their strangeness.

I’ve learned the strength of these hands. How to feel you can no longer carry any weight but do it anyways.

I want to go back in time and take care of my feet, so they know how special they are, how necessary and strong.

Please excuse a moment of gratitude: fifty-hour work weeks led to independence led to a solid savings account before turning twenty-two led to Chicago where sometimes, now, I just walk toward that sliver of a prairie sunset in the middle of downtown, a chill stirring in the bones of my fingers.

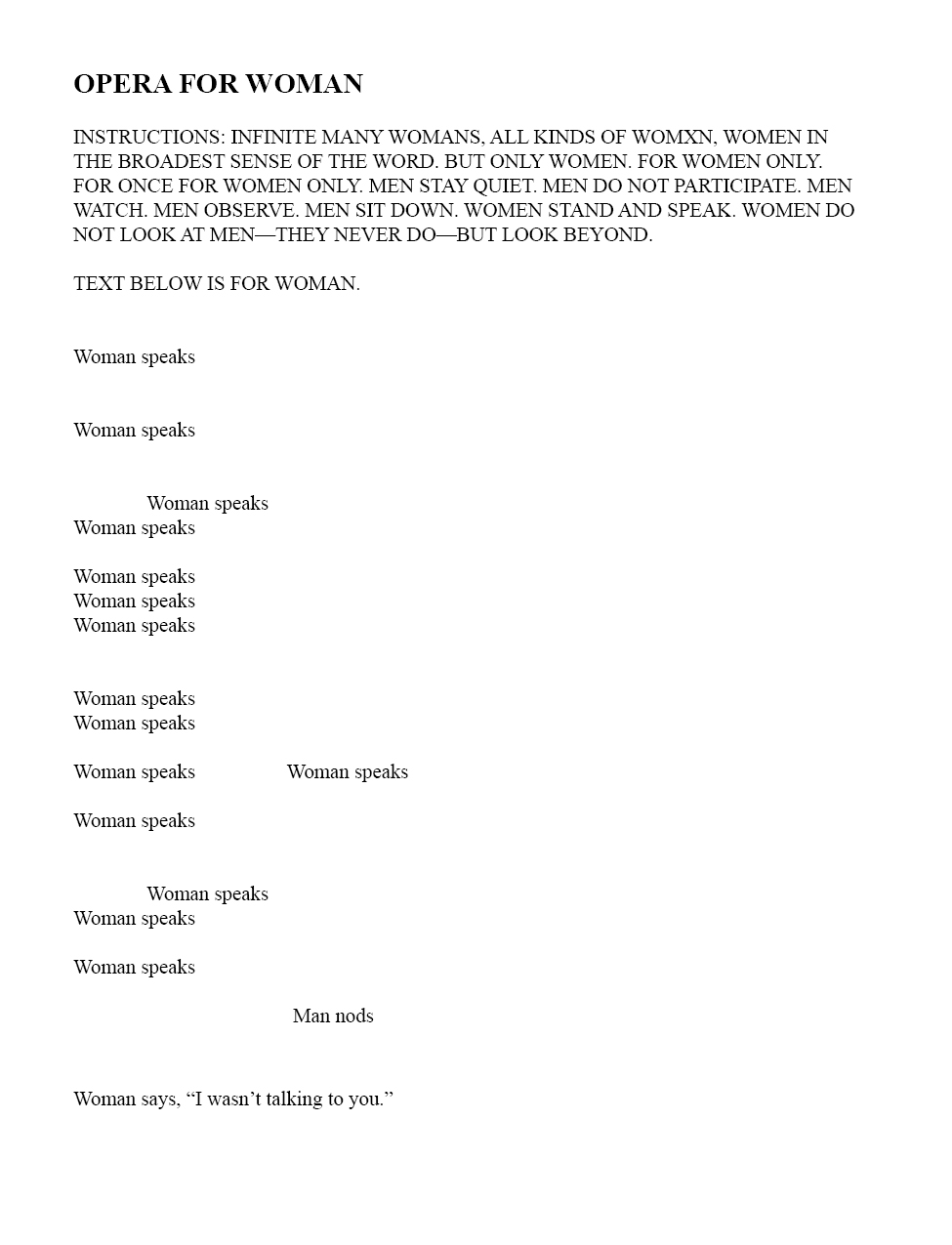

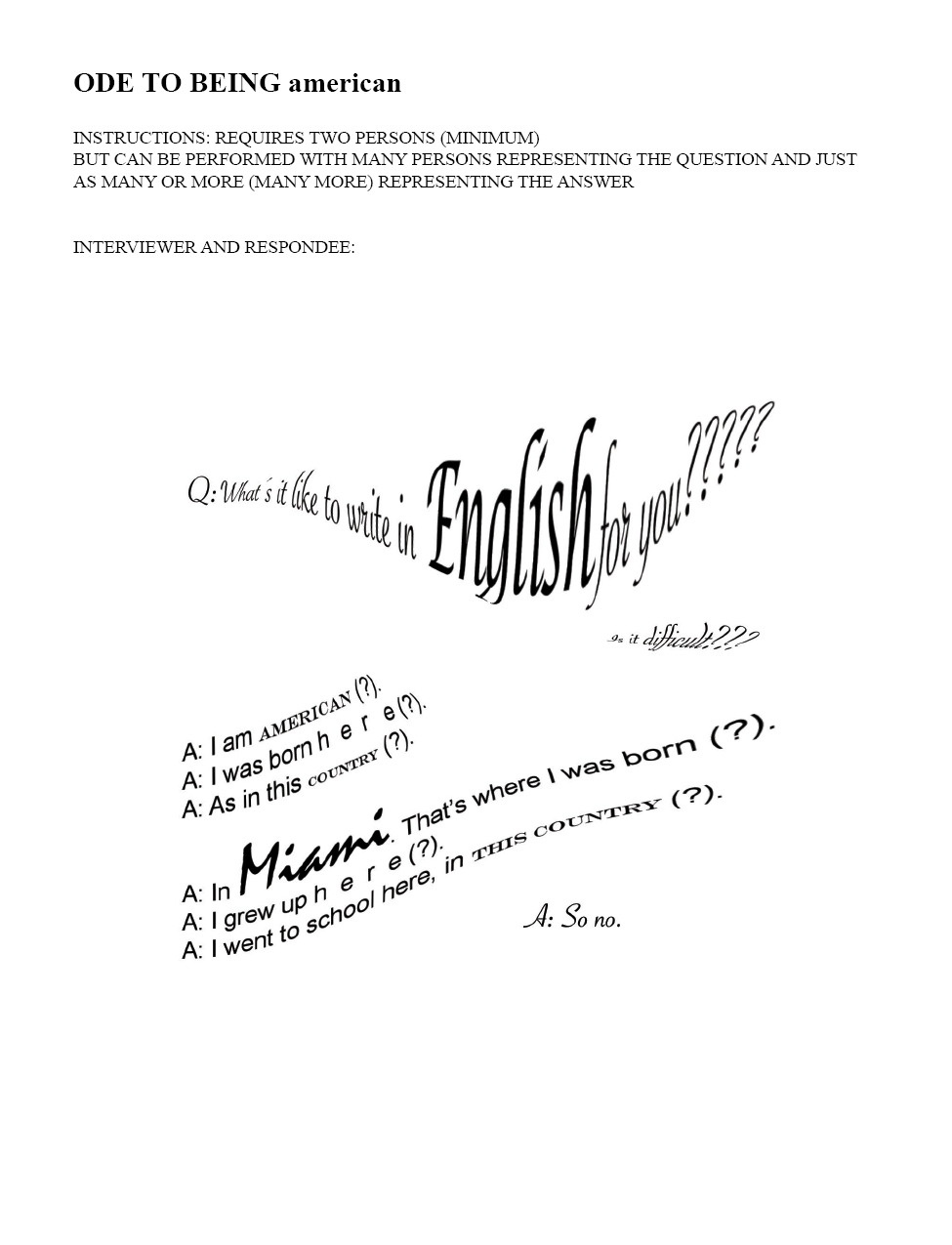

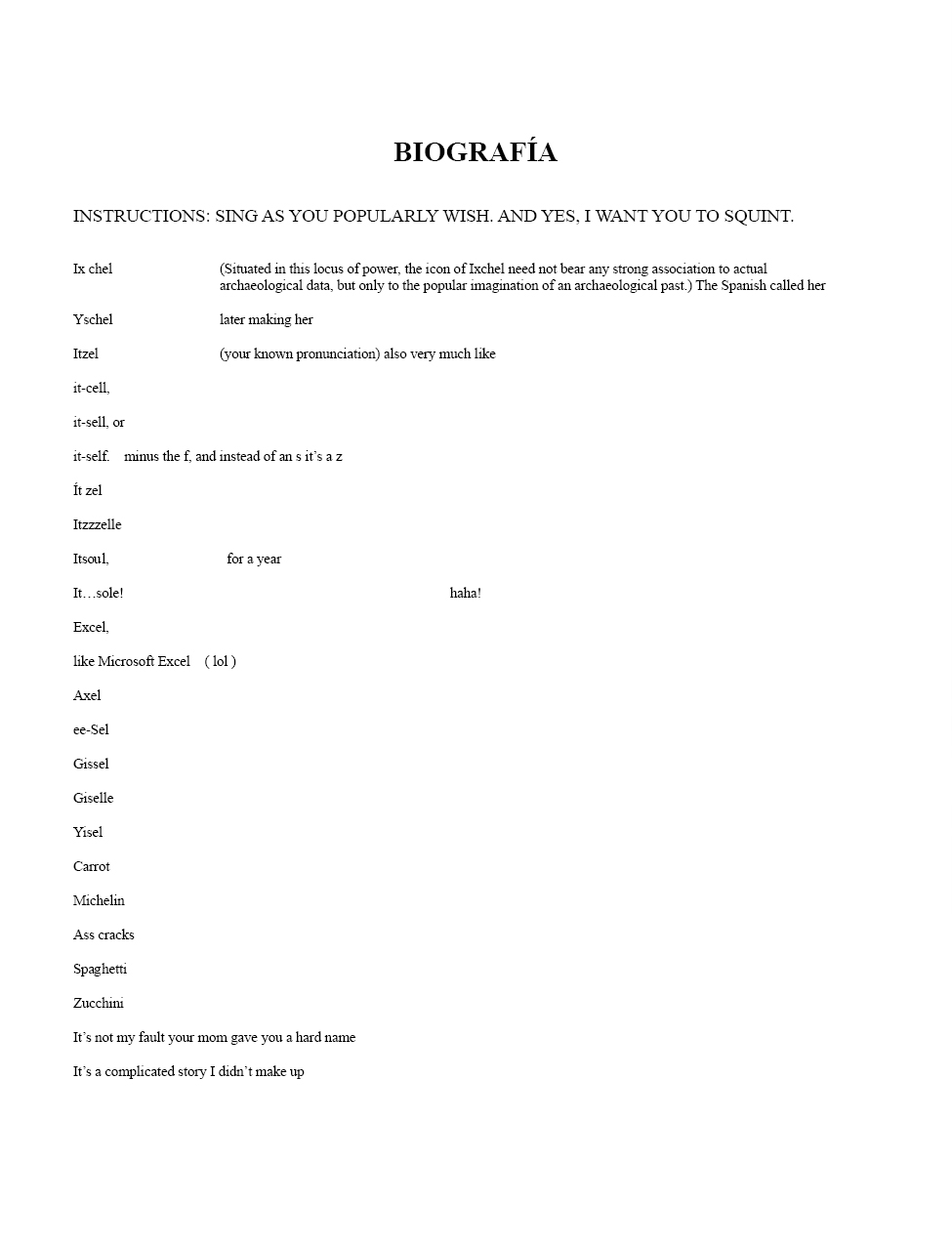

NO MORE MR. NICE GUY

itzel basualdo

to each generation a campus is born

ali tomek The Kellogg Global Hub’s façade, including one of its balconies, viewed from below. Courtesy the writer.

The Kellogg Global Hub’s façade, including one of its balconies, viewed from below. Courtesy the writer.Blue glass. Glittering glass. Glass on glass on glass.

Three years ago, this glass building was just another construction site filled with yellow cranes and orange cones and “CAUTION” tape woven into green mesh temporary fences. In 2016, when I graduated from Northwestern University, construction was booming at a rate unparalleled in my freshman, sophomore, or junior years.1 Everywhere you looked, there was something new and shiny rising out of sandboxes filled with displaced dirt: a mammoth athletic facility; the renovated arts and humanities building; a sciences library; that tricked-out residence hall; and the building that stood before me now: the Kellogg Global Hub, the university’s $250 million business school designed by KPMB Architects. I had only seen it in the Snapchat stories of fellow alumni who had visited the finished building on their trips to campus post-graduation. Now, for the first time, I was back on campus too. The Global Hub did not disappoint.

In short, it is spectacular. The building literally sparkles as the sun bounces off nearby Lake Michigan and is reflected onto the façade. It is curvaceous, undulating like the gently lapping tide. Inside, the main atrium is soaring. There are huge swathes of light.

But beyond its spectacle, there was something unsettling about this building and the others that had been completed since I graduated. Its bluish glass reminded me of the office buildings 13 miles south in the heart of Chicago’s business district, the Loop. I imagined people in crisp blue suits patrolling its corridors and I suddenly felt out of place, dressed in leggings with a chunky camera hanging around my neck, old sneakers, and an oversized sweatshirt whose cuffs were stained with splatters of acrylic paint. The other new buildings on campus featured similar corporate aesthetics that evoked 9–5 workdays and icy air conditioning and Starbucks Pike Place in venti paper cups.

A second similarity struck me: many of the newer buildings on campus had concrete neighbours. I had only recently learned about Brutalism in my graduate Art History course, excitedly discovering that Northwestern features an impressive array of these megastructures. Now, I recognised the trademark Brutalist textured concrete in the Donald P. Jacobs Center, which the Kellogg Global Hub replaced. Its next-door neighbour, the James L. Allen Center, is also of Brutalist origins. And just across the gleaming Lakefill campus stands University Library, the most infamous Brutalist building on campus, regularly maligned for its ugliness. Between the old and new, I sensed the confrontation of two very different styles.

I don’t believe this confrontation is merely aesthetic. Beyond their visual languages, these styles express a unique set of values and desires. Neither is perfect, but the danger in Northwestern’s new, corporate architecture is that it produces and propagates the very social, economic, and political realities that have come to define higher education’s most potent problems.

Fifty years ago, a parallel construction boom was taking place at Northwestern University in the form of nine buildings2 in the Brutalist style.

Brutalism began after World War II in Britain, where its iconic concrete materiality was developed by architects Alison and Peter Smithson. It was not solely an aesthetic movement, but rather an ethical one that rejected anemic British Modernism in favour of a bold, raw realism.3 The term was eventually exported worldwide, which is how it landed smack dab in the middle of Northwestern’s campus in the form of the University Library, completed in 1970.

A library is often perceived as the centre of a university’s intellectual life, but Northwestern University Library bears the brunt of the campus’ Brutalist scorn. Designed by Walter Netsch for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, it represented the school’s desire to expand its capacity for books and accommodate growing enrollment while attracting students away from its competitors. Professor Virgil Heltzel wrote in a document titled “Comments by Members of the Library Committee” that “A university library is the very heart of an institution, since it pumps the life-blood of knowledge to all departments and all schools of the university.”4 Other committee members had similar thoughts. The new library would make the school a leading library centre of the nation and unify a student body divided among different academic programmes. Its Brutalist aesthetic was intended to make “a statement to the public and the academic community. It was supposed to represent the forward thinking of the University, signal an embrace of contemporary scholarship, and set the stage for future additions to Northwestern’s new Lakefill campus,” according to the abstract included in the archives on the subject.

Though Netsch’s version of Brutalism lacked much of the ethical dimension associated with earlier versions of British Brutalism, architectural historian and critic Michael Abrahamson points out that Brutalism didn’t wholly abandon a political ethos in the United States. Here, it served as a cultural weapon against Cold War homogeneity and as an attempt to produce variety within the larger spectrum of international modernism.5 A grander rejection of conformity, while maybe not as apparent in Netsch’s designs, is evocative of Brutalism at large.

Initially celebrated, the library and the eight other Brutalist buildings on campus are now decontextualised from these aesthetic and ethical origins. While the Gothic structures on campus are admired (Deering looks like it’s from a Harry Potter movie!, exclaims every prospective freshman) the series of monumental Brutalist structures are not so well received. The encounter of the old, Brutalist structures with the new, corporate-looking ones produces palpable tension. In the old, there is materiality, the subtle play of shadows, and a historical Brutalist context that often contradicts itself. In the new, there is Instagrammable smoothness, large planes of taken-for-granted light, and easily consumed spectacle. This intimate relationship of old to new, of one style to another, illuminates the threat that Brutalism poses to the homogeneity produced by some of the campus’ newer structures, including the Global Hub. The Brutalist structures present an underlying problem to administration, specifically to the campus as a locale of tourism and as an attractive learning facility for new students. The Kellogg Global Hub is not just an abandonment of its old Brutalist home, then, but an abandonment of the library too. It re-centres campus around the concept of networking, rather than the knowledge hidden in tiny library carrels with abysmal views.

The aesthetics and organisation of the Kellogg Global Hub are active in producing new social relations on campus. The way spaces are constructed dictates the types of interactions that take place within them. Even the slightest rearrangements can produce dramatic effects. A classroom that is set up in rows, for example, fosters a less collaborative atmosphere than one arranged in a circle. Collaborative is the buzzword at Kellogg, plastered across a long purple banner that hangs from the main atrium’s ceiling and drapes two storeys down. Words like dialogue and debate, and phrases such as creative exchange are its corollaries, emphasised by the school’s leaders. Beneath its atrium, the building’s oversized Spanish Steps are its main feature, modelled after the famous staircase in Rome. Set in two enormous stacks, they provide a welcoming rendition of the academic environment. But the stairs promote casual interaction and light socialising much more than engaged debate: pitches and a subtle hierarchy à la the CW’s once-beloved Gossip Girl and the high school hierarchy delineated by the steps of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (No one sits higher than me!, shrieks Blair Waldorf). This hierarchy is already enforced in other parts of the building, where nearly every auditorium, classroom, study room, and air space is named with a plaque recognising its donors.

The building’s access issues secure its hierarchies. If the atrium is remarkably open, the Global Hub’s four wings are remarkably closed off as the offices of faculty and private classrooms. Every door is barricaded by a small, black card reader that projects green or red light, indicating its status as either an open room or one reserved for the card-holding elite. The building features a number of curvy balconies beyond the transparent, interior glass office and classroom walls—in stark contrast to the ordinariness exuded by its Brutalist neighbour—but it is unclear how to access these balconies without tromping through a series of cubicles and suspicious stares, all located behind one of the deterrent black card readers.

The main atrium produces a sense of surveillance that promotes the rise of the managerial class on campuses. It reminds me of the multi-storey glass enclosures featured in Apple stores, and affords the inclusion of large, open work and event spaces that are reminiscent of anonymous cafés. The architect Rem Koolhaas’ concept of the Generic City comes to mind: “The apparently solid substance of the Generic City is misleading. 51% of its volume consists of atrium. The atrium is a diabolical device in its ability to substantiate the insubstantial.”6 Here is where the building begins to assert something not just eerie, but all too real along the lines of: the university may seem solid, but is actually run by 51% “air” or “fluff,” i.e. the rise of the administrative, managerial class. In a 2015 New York Times piece, Fredrik deBoer notes that it is not uncommon for senior administrators to outnumber professors on college campuses.7 While remarkably open (as atriums tend to be), this one suddenly produces a haunting sense of top-down surveillance. Architectural historian Reinhold Martin describes this surveillance as the initial product of Cold War computer rooms that was then adopted into the structure of modern corporations.8 The main atrium resembles these Cold War corporations as “models of casual sociability and neatly packaged novelty, symptoms of an enforced togetherness”—Kellogg’s buzzword collaboration again comes to mind here—“under the sign of a consumerist ‘global village.’”9 Indeed, in Blair Kamin’s review of the building for the Chicago Tribune, he praises its atrium, but also calls atriums the prominent feature of business schools.10

The Kellogg Global Hub embodies a celebration of the United States economy after the Great Recession. What is remarkably absent in the building’s design is any engagement with what went wrong in 2008: the bailouts, the failure to prosecute any top bank executives, and the millions of Americans who lost their homes when the housing bubble burst. This lack of criticality is reinforced in the building’s name. The Chicago Tribune review notes that the new building is “portentously named the Global Hub,”11 and a 2017 piece written by alumnus Jeff Rice for The Daily Northwestern contextualises the university’s increasing desire to “go global.”12

Part of the global initiative involves expanding the Northwestern brand in the vein of New York University’s failed effort to establish campuses worldwide. In Rice’s words, “the committee’s proposal begins to look like a new kind of educational colonialism; the arrogance and insensitivity by the task force makes me cringe.”13 This criticism prompts a series of questions: in the vein of early Brutalism’s ethical dimension, what is the Global Hub really committed to? What makes it global? There are flags from about 50 countries hanging in neat rows in the Hub, but what do they symbolise? The school identifies a sympathetic question about how to situate institutions in a new, increasingly interconnected world. But instead of sincerely investigating that question and determining the stakes of it, it appears more like an exercise, one that proclaims the centre of the world is located on the shores of Lake Michigan.

What is also at stake in this building is the support of another bubble: the one formed by heavily inflated tuition prices. It is here, in its atrium, where consultants are born. Names like Deloitte and McKinsey and Bain form a shared language that unites the disparate worlds of science and humanities majors (not unlike the way committee members initially conceptualised University Library as a unifying force). As the late Marina Keegan wrote in The Opposite of Loneliness, 25% of her graduating class at Yale went into consulting. She expressed concern about such a significant number of students entering one profession and since the book was published in 2014, that number has only risen.14 Institutions provide access to the recruiters who descend upon universities in search of cogs that can operate their Excel spreadsheets for a handsome six-figure salary. Commercial-looking buildings become a method for the school to communicate with the corporate world, specifically to support the rise of the consulting industry that has the ability to prop up the cost of tuition and the value of a degree. These buildings oppose the imaginative origins of American Brutalism, which asserted the value of creation (over crunching someone else’s numbers). They transform students into commodities, rather than consumers. Students are exchangeable and generic—anyone can be a consultant! In the middle of this bubble is architecture, which is now starting to look more and more like a banal mall-slash-corporate playhouse at Northwestern and on campuses nationwide.

Like this new campus-corporate aesthetic, Brutalism was not a perfect style. There are many aspects of University Library, for example, that are no longer programmatically ideal. The tiny carrels on its upper floors are isolated and downright creepy at night. There is also irony in the fact that today’s managerial campus architecture resembles the same kind of top-down approach adopted during the Cold War era in the pursuit of a Brutalist campus: “What manifestly underlay the trajectory from the Brutalist building to the megastructure was the belief, or hope, that bigness—a total architecture, generated by teams of specialised designers and planners—could somehow control the late-20th-century city’s daunting chaos and complexity.”15 Late Brutalism, in fact, had much in common with the corporate architecture of today. Both embody moments of university expansion. This shift toward bigness and total style also represents the beginning of Brutalism’s failure. It bears similarities to the way corporate architecture manifests on campuses, as well as on Wall Street post-2008 Recession—some institutions are apparently too big too fail. But at its best, Brutalist architecture represented an empowerment of civic duty in the United States—a belief in the possibility of the institution, and an embrace of content over slick styling. Its failures should inform this generation’s campus buildings.

Architecture on campuses is not just the reflection of already-implemented social, economic, and political phenomena. It is, rather, a primary way these trends are introduced, developed, and mediated in the physical world. The Kellogg Global Hub is evidence that architecture is not just a symptom of the problems in higher education—the rise of administrators and student loan debt—but a cause. If we want to improve higher education, perhaps we should start by designing buildings that acknowledge and improve upon its failures.

1 According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, Northwestern was fourth among all private universities in total dollars spent on new construction for the 2016–17 fiscal year. “On Which Campuses Is Construction Booming?” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 3 May 2019.

2 By my own count.

3 Joan Ockman, “The School of Brutalism: From Great Britain to Boston (and Beyond)” in Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston, ed. Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2015), 32–33.

4 Documents referenced are located in the Northwestern University Archives. Date of the quote is 7 January 1953.

5 Michael Abrahamson, “North America: An Introduction,” in SOS Brutalism: A Global Survey, ed. the Wustenrot Foundation (Zurich: Park Books, 2012), 117.

6 Rem Koolhaas, The Generic City (New York: The Monacelli Press, Inc., 1995), 1262.

7 Fredrik DeBoer, “Why We Should Fear University, Inc.” The New York Times, 9 September 2015.

8 Reinhold Martin, The Organizational Complex (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 2–13.

9 Ibid.

10 Blair Kamin, “Northwestern’s new business school home promises valuable lessons,” Chicago Tribune, 24 March 2017.

11 Ibid.

12 Jeff Rice, “Rice: The hidden costs of Northwestern’s global expansion,” The Daily Northwestern, 3 January 2017.

13 Ibid.

14 36% of Harvard’s 2017 class entered the consulting or finance industries. Chris Hopson, “The Draw of Consulting and Finance,” Harvard Political Review, 15 July 2018.

15 Ockman, “The School of Brutalism,” 44.