fugere urbem: aesthetics, politics, and class

in violeira’s languages of the non-urban

cecília resende santos

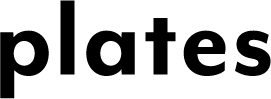

The rainy season is a problem for Violeira, an area located a 20-minute drive away from the city centre in the municipality of Viçosa, in the interior of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Every year, residents complain to each other and city government about the downpour’s impact on the dirt roads: intractable mud, undrained puddles, and, once the ground dries, deep rifts that rattle the bodies inside passing cars. At times, the damage can complicate journeys into the city for work, school, or the grocery store. The issue embodies a broader uncertainty about (and dissatisfaction with) the scope of the city’s duties towards a community that is seen, and sees itself, as outlying.

The idea of paving the dirt roads has gained ground as year after year streets surrounding Violeira are covered in asphalt or concrete blocks and new neighbourhoods are carved out of the hills. But the dirt roads are key to the neighbourhood’s self-definition, and new pavement could mean a categorical shift, inviting more development and changing the area’s relationship with the city. The roads have become the material and symbolic nexus of a larger discussion about the present and future character of Violeira, challenging its self-definition as a rural place.

The Violeira I grew up in more than a decade ago was unequivocally a “roça”—a Brazilian word rooted in agricultural practices and broadly designating a non-urban place. Surrounding the Turvo Sujo river valley, Violeira is moderately dense, but strewn with pastures and small fields of beans and corn beside houses with vegetable gardens and fruit trees. The roads, crucially, are unpaved, and there is no street lighting. We have terms for these elements: streets are called roads (estradas); residencies are ranches, land, or properties (sítios, terrenos, propriedades); when we left for school, work, or shopping, we would “go to the city,” while our city-dwelling friends would “go to the roça” to visit us. Together, these terms form the aesthetic and social codes of the rural. This language structures public debate and informs the urban policy and laws that determine the region’s future—even when, as I found out, it might not match the definitions in the city’s zoning codes.

Many of the issues of land use and shared infrastructure being debated in Violeira relate to urban policy and legal codes that, at least on paper, regulate development. More broadly, residents’ debates and demands concern the scope of the city government’s responsibility for Violeira, which currently appears unclear. Despite my family members’ and former neighbours’ insistence on the legislation’s irrelevance, I decided to consult Viçosa’s zoning law and building code for its interpretation of Violeira.

There are two main pieces of local legislation that describe the city geographically and determine guidelines for its occupation: the “Plano Diretor” or Master Plan1 and the “Lei de Ocupação, Uso do Solo e Zoneamento,” or Zoning and Land Use Law.2 The Master Plan establishes the goals, obstacles, and directives for the municipality’s social and economic development, while the Zoning and Land Use Law defines terms, zones the municipality, and more closely determines each zone’s requirements and restrictions for subdivision, construction, and economic land use. My neighbours’ scepticism of these documents is unsurprising: Viçosa’s Master Plan, instituted in 2000, has faced a legislative gridlock over its revision since 2014;3 the Zoning and Land Use Law, also from 2000 and once altered to be part of the Master Plan, is now threatened with exclusion.4 While they might not work as active and enforceable regulations, the texts remain an important reference guide to the lexicon of the debate.

The two documents each describe residential, central or commercial, industrial, rural, and university zones, aggregated into three macrozones: urban, rural, and university (Viçosa is home to a federal university best known for its agricultural science programme). Additionally, the Master Plan delineates two “urban expansion” macrozones. To my surprise, both documents include Violeira in the urban macrozone,5 even though the term “rural zone” is regularly used to refer to Violeira in conversations, newspapers, and even by public officials (while “roça” is open for interpretation, “rural zone” seems factual and legalistic, implying knowledge of actual policy). The popular terms suggest an emergent set of conventions and expectations regarding lifestyle, economic activities, architecture, and spatial occupation separate from the “rural” presented in legal documents.

If Violeira is urban, what counts as rural in the formal language of public policy? While I had been observing the rural as a holistic descriptor encompassing personal and social values, both the Master Plan and the Zoning Law define the rural primarily by economic activity. The Master Plan’s only section exclusively on the rural zone, “Guidelines for Rural Development,” is within the “Economic Development” chapter.6 The Zoning Law defines the rural zone as “dedicated to agricultural, cattle, extractivist, agroindustrial and foresting activities,” and adds that “subdivision of land for urban purposes is not allowed.”7

In both documents, the word “rural” often appears alongside and opposed to “urban,” generally to outline inclusive planning and development practices (“to connect urban and rural areas to the transit system” or “to guarantee access to urban and rural space”).8 In turn, the word “urban” appears more often, typically modifying words like “infrastructure,” “policy,” and “transit,” as well as in derivative forms, above all “urbanisation.”9 As a public policy term, “urbanização” (urbanisation) means installing public (shared) infrastructure, regularising streets and properties, establishing access to public services like mass transit and utilities, and generally integrating a place to urban grids and functions. These uses indicate that public, state, or civic structures, rights, and responsibilities are coterminous with the urban. Rural space is not entirely ignored or unregulated, but it is a marginalised territory for services like housing, utilities, and infrastructure policies (i.e., urban policies). Truly rural spaces, as defined by the law, are the purview of economic development policies much more than human or residential ones. Meanwhile, locations like Violeira, characterised by increasing informal development and weak rural economies, find themselves in an awkward limbo.10

Violeira’s status as an urban zone suggests that it is entitled to every resident-oriented public service and shared infrastructure described in the Master Plan, and subject to obligations like construction permits, sidewalks, and urban property taxes. This, however, contradicts what I always heard and expected: that Violeira does not have certain infrastructures, including road pavement and government-provided electricity and running water for all buildings, because it is rural; that landowners benefit from paying the (lower) rural property tax; that the irregularity in land subdivision and use is allowed by its marginal legal status.

Violeira’s reality is partially reflected in legislation, in that the spatial planning parameters set in the Zoning Law and the Master Plan distinguish it from other urban residential areas. These distinctions are most clear in the Master Plan’s specifications of Violeira’s main zoning area. The zone is described as accommodating “predominantly unifamiliar and residential use, with restrictions to density and height,” where “only one autonomous unit is allowed per lot.”11 Several restrictions to economic activities and services apply to Violeira’s streets according to the Zoning Law: retail and diversified commerce, personal and health services, social assistance, educational institutions, and public service administration are not allowed.12 These policies suggest a special class of semi-urban occupation.13 Yet they do not reflect the imaginaries expressed in the everyday language of the residents, nor do they match popular explanations for the lack of public services. If anything, that Violeira has always been legally urban means that the emergent, practical, and symbolic definitions of the rural are more consequential than I had imagined.

The last time I visited Viçosa, I walked through the neighbourhood with my father. He has always commented on its developments and the negligence of public authorities, and in 2017 he started a Facebook group with other Violeira residents to report on new and recurrent issues with the roads.14 A professor of agroecology at the Federal University of Viçosa, he moved to Violeira in the 1980s as a student, eventually building his own house there. He was part of a wave of students and professionals who sought out rural life, sustainable agriculture, and alternative lifestyles. For them, and others who followed, the rural held something aspirational, which contributes to many contemporary residents’ resistance to changes in the local landscape.

Before them, there were local farmers and their families—the major landowners in the area, though most now sustain themselves primarily through selling or renting land for residential use rather than agriculture. As the local agricultural economy weakens and younger generations pursue other careers, the original farms are subdivided through sale or inheritance, and ever-denser residential occupation replaces the fields. In this context, local landowners stand to profit from this change. And yet the region’s pastoral character remains a central point of self-identification and attraction for old and new residents.

As I stroll through Violeira with my father, the neighbourhood’s trajectory is conspicuous in the built environment. He points out the new developments, mentioning previous landowners by name, and identifying changes around the older houses. Seu Saulo’s house, he tells me, is unchanged, near the football fields in the floodplain of the Turvo river. He calls it a “casa de roça”: an older, simpler, and smaller farmer’s house surrounded by subsistence crops. I cling to this precious nugget of vernacular typology. He gestures towards a cluster of newer houses up the road, each built by Saulo for one of his daughters—not for living, but for rental: an investment in their futures. Larger, brightly coloured, and densely packed, they resemble an urban street. Up the hill and across the road, a new driveway splits Saulo’s former pasture in two, with four lots on each side. These new rental houses that hug the road replace the casa de roça’s typical long driveway.

Despite this more city-like occupation, some new constructions preserve certain rural characteristics, signalling persistent perceptions and desires about Violeira. Among these symbolic architectural elements are wooden gates, barbed wire fences, driveways paved with gravel or gneiss, wooden shutters, pingo d’ouro hedges, and low-slung rectangular houses. The professors’ houses are more elaborate, incorporating salvaged materials, soil-based wall paint, and colonial-style farmhouse elements—indicators of taste and class that still appeal to a rural imaginary, lying somewhere between old plantations and eco-friendly homesteads.

It would be superficial (though not false) to conclude that Violeira is becoming an urban neighbourhood in rural clothing. In significant ways—both legally and in real estate development culture—Violeira remains “rural.” While Violeira is not technically in a rural zone, it is still largely rural properties: portions of land registered under “rural deeds” (escrituras rurais), and passed down in the original farmers’ families. Though the minimal legal area for rural land subdivisions is one rural module, calculated for agricultural uses, properties on rural titles are often informally divided and sold in smaller lots.15 Requirements and services implemented in other urban areas (and also applicable to Violeira’s zone), such as sidewalks, regulated building heights and setbacks, postal and utilities services, and street and traffic systems are not established. The rural persists within a technically (and, increasingly, de facto) urban condition, and with it persists the relative marginalisation afforded to rural populations.

What is Violeira’s future? Increased density (thus far unregulated) will call for land use diversification: commercial, educational, and institutional structures might appear. In a growth spiral, this diversification will demand additional infrastructure—the roads will be paved—which will, in turn, stimulate development. Violeira’s current informal developments are not suitable foundations for urbanisation policies. At several points, there is no room for sidewalks or expanded two-way streets; the ad hoc system of roads, extensions, and semi-private access streets will complicate circulation and service delivery; the patchwork of on- and off-grid electricity and water systems will make for contentious integration; and the only solution for land deeds is batch regularisation. Piece-meal development increases urban infrastructure demands while making it harder to implement them.

Desires for Violeira’s future seem divided along generational and class lines. For most older farmers and their families, for whom land real estate has supplanted agricultural activities, more development (in all its senses) is welcome. Street infrastructure and property regularisation would be both convenient and profitable, and even a sign of progress. For some newer residents, the preservation of Violeira’s rural je ne sais quoi seems more important. To many, it is the main reason for moving there: to own land and to be away from traffic, noise, and neighbours—fugere urbem.

Driving out of the neighbourhood with my father, I saw Violeira’s potential future in two types of marginal development. On one end, gated communities encircled by walls present a semi-isolated urbanism for the middle and upper class, with large houses and large backyards outside the city’s tumult.16 On the other, labyrinthine neighbourhoods like Cantinho do Céu, dotted with small houses and narrow unnamed streets in many pavements, are already engulfed by the city but remain cut off from services like transit and garbage collection. Considering the divisions over the fate of Violeira’s own roads, I can’t help but think that its future, too, will be split.

1 Plano Diretor, Viçosa (MG) L. 1383 (2000).

2 Lei de Ocupação, Uso do Solo e Zoneamento, Viçosa (MG) L. 1420 (2000).

3 “Especialistas questionam minuta do novo Plano Diretor,” Jornal Folha da Mata, 5 May 2017.

4 “Lei de Uso e Ocupação do Solo ficará fora do Plano Diretor,” Jornal Folha da Mata, 25 February 2020; Ítalo Stephan and Luiz Fernando Reis, “Revisão do plano diretor de Viçosa: participação popular e auto-aplicabilidade,” Risco 6.2 (2007), 84–93.

5 The Zoning Law mentions it in the residential zones ZR1 and ZR3 (L. 1420/2000, Anexo V), while the Master Plan places it in Z3 and Z5 within the urban macrozone, MZUr (L. 1383/2000, Anexo B, Mapa 1 and Anexo D, Mapa 2A).

6 L. 1383/2000, Art. 35. On Art. 7 in L.1420/2000, “agricultural economy” is counterposed to “urban economy,” once more suggesting that the non-urban is defined by its economic activities.

7 L. 1420/2000, Arts. 76 and 77.

8 See, for example, L. 1420/2000, Arts. 3, 4, 8, 25, 27, and 33. The word “rural” appears 10 times in the Master Plan.

9 Art. 46 in L. 1420/2000, within Sec. I “Urban operation” under c. V “Urban policy instruments,” expresses this most eloquently: “Urban operation is the set of integrated interventions and measures to make possible special urbanistic projects, observing the public interest, in previously determined areas.” See also L. 1420/2000 Arts. 6, 7, 18, 22–25, 27, 30, 47–50. In total, words deriving from “urban” appear 56 times in the Master Plan.

10 These conditions have proven profitable to some: residents who inherited land in the area, and, above all, construction and real estate companies developing gated communities.

11 L. 1383/2000, Anexo E, Quadro 10.

12 L. 1420/2000, Art. 84, Anexo II.

13 Interestingly, some of these requirements and restrictions are also shared with Z4—the zoning code for gated communities (ibid.).

14 “About,” Estradas da Violeira Viçosa MG [Facebook group], retrieved 27 July 2020.

15 “Módulo rural” (rural module) is a unit of agrarian land, expressed in hectares, used to compare rural properties for evaluation, benefits, and legal purposes. According to the Zoning Law, the size of rural properties shall not be inferior to one rural module (L. 1420/2000, Art. 77).

16 Significantly, these communities are known in Viçosa to abuse city services when they are technically required to manage their own refuse and sewage.